In Australia, hazardous manual tasks remain the leading cause of workplace injuries. Body Stressing accounts for 36% of recorded injuries, followed by 22% of injuries being caused by falls, slips and trips. These are often caused by a combination of complex factors, such as poor equipment, poor workplace layout, uneven, sloping / slippery surfaces, spills and a workforce that is rushing. (Safe Work Australia, 2023).

Organisations are increasingly recognizing the need for effective strategies to mitigate these risks and are constantly looking to better and easier ways of understanding the complex causes of body stressing injuries.

What is a Hazardous Manual Task?

Let’s start with the definition for a Hazard:

A potential source of harm.

And the following is often a definition used to describe a Manual Task:

Any physical activity involving the use of the body,

such as lifting, pushing, pulling, carrying, or holding objects.

A manual task becomes ‘hazardous’ when repetitive movements, awkward postures, forces, vibrations and sustained positions for long periods of time are involved. And let’s add the layer of psychosocial workplace and individual factors that exist in any workplace that gives rise to a heightened individual stress response, increasing fatigue and reducing internal tolerance. (Oakman and McDonald, 2019)

All of these factors can pose a risk. To effectively identify hazardous manual tasks, a comprehensive risk assessment is a MUST (Buckle & Devereux, 2002). Most businesses struggle to understand the complexity of reducing risks associated with hazardous manual tasks. They are also looking for solutions with maximum reduction in risk, and minimum interruption to operations.

Why should a Business conduct Manual Task Risk Assessments?

Conducting a risk assessment offers numerous benefits:

- Identifying Hazards: Pinpoints potential risks in the workplace (ISO 45001:2018).

- Improving Safety: Enhances employee safety by implementing measures to mitigate risks (Hale & Hovden, 2015).

- Compliance: Ensures adherence to legal requirements, avoiding penalties (Safe Work Australia, 2023).

- Informed Decision-Making: Provides data to support safety policies and resource allocation (Tucker & Smith, 2004).

- Prioritizing Risks: Enables focused action on the most critical issues.

- Enhancing Productivity: Reduces workplace incidents, leading to less downtime (Gibb & Smith, 2007).

- Fostering a Safety Culture: Promotes a proactive approach to workplace safety.

- Continuous Improvement: Establishes a framework for ongoing safety evaluation.

- Employee Engagement: Involves employees in the safety process, enhancing awareness and commitment (Dahl & Løvseth, 2020).

- Protecting Reputation: Demonstrates a commitment to safety, enhancing organisational reputation.

Overall, risk assessments are a critical component of effective workplace safety management.

How is Big Business Tackling Hazardous Manual Tasks?

Australia’s largest organisations are adopting various innovative approaches to assess and manage hazardous manual tasks:

1.Wearable Technology

a) Some of the Pros

Wearable devices are increasingly being used to monitor physical movements and posture, in real-time. These devices provide objective data on how employees handle tasks involving lifting, pushing, or carrying, helping to identify ergonomic risks and improve safety.

- Monitoring Movements: Wearables track body movements, identifying unsafe postures or repetitive patterns (Kumar et al., 2016).

- Real-Time Alerts: Devices provide immediate feedback on improper lifting techniques.

- Data Collection: Objective data helps safety managers identify high-risk tasks and improve manual handling processes.

- Reducing Injuries: Continuous monitoring can prevent injuries before they occur.

- Fatigue Monitoring: Some devices help ensure workers are not over-exerting themselves.

b) Some of the Cons

Evidence tells us that changing techniques (the approach of lifting) has no impact on risks associated with Manual Tasks. Most controlled studies of training have shown it to be ineffective in reducing accidents and injuries related to lifting (NIOSH, 1981; p.146).

So, although wearable technologies claim to give real time feedback to users that a task they are completing is using a particular muscle group or posture to excess, there is no evidence to support in the long term that they will change their approach to the task after receiving feedback.

There are other cons, they cost a lot, they often rely on the user to fit them properly or you need more than just the user to fit them (more resources). They may be dependent on a good Wi-Fi connection, the sensors can look and feel obtrusive in a work setting, additional resources like filming equipment can be obtrusive and it often raises privacy issues etc. Whilst they may produce a plethora of data on how the user was working, they don’t necessarily provide a risk score (which can result in the organisations becoming overwhelmed with what they should do with their data).

And in the absence of training on how to then use the data to identify higher order (more effective) risk controls that design out the hazardous component of the manual task, they are useless.

2. PErforM Program

PErforM is a participative manual task risk management program that engages employees in identifying and assessing risks associated with their tasks. By involving the team, organisations can foster a culture of safety and continuous improvement (López et al., 2017). (https://www.safework.nsw.gov.au/hazards-a-z/hazardous-manual-tasks/perform)

It is free and there is an online version, but it does not provide a risk score and therefore organisations find it hard to prioritise which manual task is riskier than another and then struggle to focus on which one to tackle first. Often, they will pick the easiest one to solve, with less effective lower order risk controls.

3. The APHIRM Toolkit

Developed by the Ergonomics and Human Factors team at La Trobe University, the APHIRM (A Participative Hazard Identification and Risk Management) Toolkit aims to reduce musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). This comprehensive framework emphasizes collaboration among stakeholders and ongoing dialogue about safety practices. It is also free, and it involves workers coming up with solutions, it can also incorporate psychosocial impact on employees, and it provides an action plan. It does require training in use of the APHIRM toolkit (at least a day) and is resource intensive in involving the workforce in coming up with solutions. (https://www.aphirm.org.au/)

Getting Hazardous Manual Tasks “Handled”

Despite the adoption of various strategies, hazardous manual tasks continue to be the leading cause of injuries in Australian workplaces. This underscores the need for a proactive safety culture that engages employees, provides continuous training, and encourages open communication about risks.

As Australia’s organisations explore a blend of modern technologies and traditional methods to assess hazardous manual tasks, the focus must remain on creating a holistic approach to workplace safety.

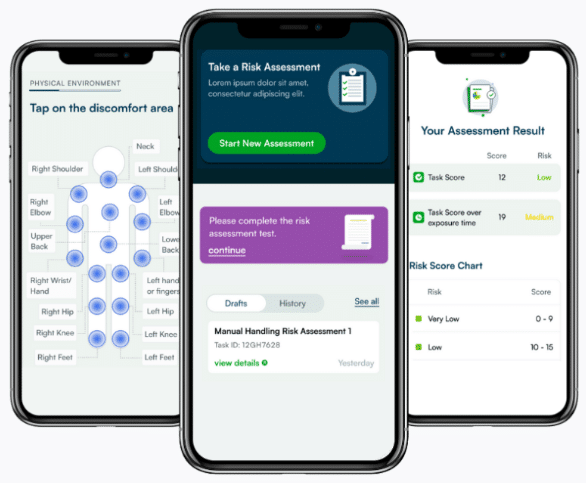

At Productivity Matters, we are introducing ‘Handled’, a digital application that empowers employees to assess manual tasks. Handled will produce a Risk Score as it uses complex algorithms to understand exposure (time) impacts while it looks at psychosocial and environmental impacts too. It has been developed by Certified Professional Ergonomists, who have worked in industry for over 30+ years. Best of all ANYONE, will be able to use it. You will need very little training to understand how to assess a manual task and it will produce a risk register for your business.

Watch this space:

Beta Testing of Handled is due to commence in March 2025,

a go live date is planned for June 2025 and you can now follow Handled on Instagram too!

References

- Buckle, P. & Devereux, J. (2002). The Effects of Ergonomic Interventions on Musculoskeletal Disorders in the Workplace. Occupational Medicine, 52(8), 481-488.

- Dahl, A. & Løvseth, L. (2020). Employee Engagement in Health and Safety: The Role of Workers in Risk Assessment. Journal of Safety Research, 74, 151-158.

- Gibb, A. & Smith, R. (2007). Safety Management Systems: A Study of Industry Best Practices. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 133(1), 23-30.

- Hale, A. R. & Hovden, J. (2015). Management of Safety: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Safety Science, 76, 14-29.

- Kumar, S., Jha, S., & Ghosh, M. (2016). Wearable Technology for Ergonomics: A Review. Ergonomics, 59(4), 427-439.

- López, G., Llamazares, M., & Galvez, M. (2017). Participative Ergonomics: A Case Study in the Construction Industry. Applied Ergonomics, 65, 123-130.

- NIOSH. 1981. US Department of Health and Human Services. Work Practices for Manual Lifting.

- Oakman, J., Macdonald, W. The APHIRM toolkit: an evidence-based system for workplace MSD risk management. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord 20, 504 (2019).

- OSHA. (2020). Risk Assessment: A Guide for Employers. Retrieved from [OSHA website].

- Safe Work Australia. (2023). Key Work Health and Safety Statistics 2023. Retrieved from [Safe Work Australia website].

- Tucker, S. & Smith, M. (2004). Using Data to Drive Safety Improvements: A Framework for Success. Journal of Safety Research, 35(1), 53-63.